This was written by Sarah Finnie Robinson. It originally posted on Medium:

What do People Really Think About Climate Change? (Tweet this) It Depends on How You Ask Them.

It turns out we’ve been asking the wrong question.

It’s not Do you believe in climate change, as in do you believe in the tooth fairy.

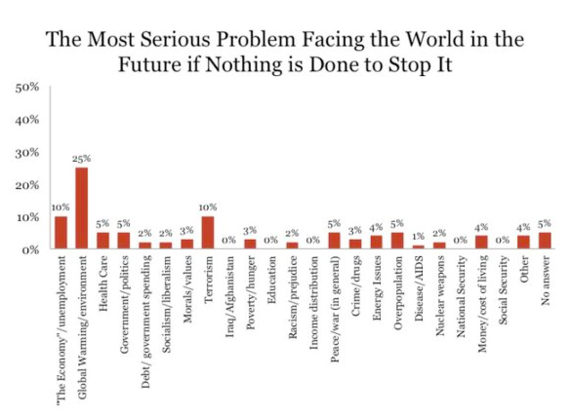

It’s also certainly not What is the most important problem facing this country today?, as George Gallup began asking in 1930s. Because when people are asked this question recently, the environment has ranked last every time — beneath jobs, healthcare, education, security, infrastructure, terrorism, kids, housing, transportation and other important concerns.

Now tweak the question:

What will be the most important problem facing the world in the future if nothing is done to address it?

Remove constraints of nation, moment, and inaction — and global warming zooms to the top.

For two decades, this kind of data has been collected by a team of social scientists at Stanford’s Political Psychology Research Group (PPRG), led by Dr. Jon Krosnick. Krosnick’s carefully constructed questions get to the heart of American public opinion on global warming. The results are consistent, powerful — and they can be motivating.

Social norms are the bedrock of behavioral science. People are encouraged if they see consensus on a belief. When trusted friends and experts are in agreement — on an idea, a product, a person, a destination — we are encouraged to act, individually and collectively.

You have observed this since kindergarten.

The new Stanford findings on global warming, presented June 9 at the Metcalf Institute, should promulgate crowd-driven insistence on prompt and sweeping action to reduce carbon emissions. Yes, the world is slowly considering serious reductions to dangerous CO2 levels, thanks to herculean efforts by governments, philanthropists, business leaders, academics, and others — the Paris Agreement is a milestone for this commitment. However, experts warn we are not progressing quickly enough.

Simply by asking the right questions, we now know how the American public feels about climate change. The results are dizzying.

Examples from PPRG’s 2015 data:

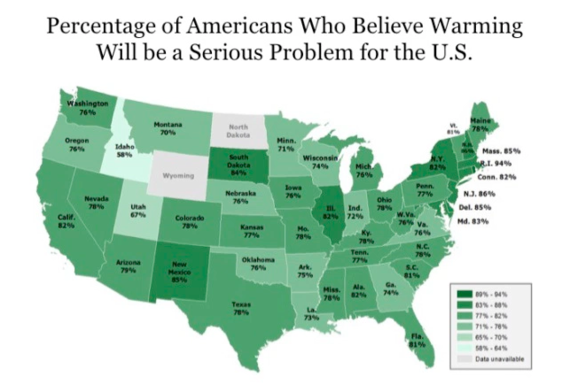

- 74% of Americans believe that global warming will be a very or somewhat serious problem for the U.S.

- 83% of Americans believe that global warming will be a very or somewhat serious problem for the world.

- Only 9% of Americans are extremely/very sure that global warming has not been happening.

- Should the U.S. government limit emissions by American companies? 78% say yes.

“These majorities are huge,” says Krosnick. “We rarely see three-quarters of Americans agreeing on something!”

The PPRG team concatenated national surveys to produce measurements of opinion in 47 states and found patterns such as this:

“On so many issues, Americans are divided about 50–50, but that’s not true of climate change,” Krosnick adds. “We see that a large majority of Americans believe that global warming has been happening, attach a high priority to it for government and individuals to address, and support a variety of policies to reduce carbon emissions and mitigate impacts,” such as sea-level rise and extreme weather.

Alexander Verbeek, founder of the Planetary Security Initiative, observes that many people are beginning to experience climate impacts in a personal way. Maybe you were planning to go to Paris, with the Mona Lisa on your bucket list. But Paris experienced a 3-day deluge early in June, causing Louvre curators to hurriedly move treasures of art and antiquity to higher ground. Museum-goers had to revise their plans. A prompt analysis by scientists at World Weather Attribution estimates that global warming increased the possibility of such extreme precipitation by 80% for the Seine River basin.

People noticed. The French Open tennis tournament was delayed, the metro closed, and riverside cafes were shut.

Behavior changes when you simply cannot carry out your plans as expected — and awareness builds.

Verbeek predicts that social conversations will soon be about the moment you realized that you were witnessing climate change for the first time. “It will be the ‘Where were you?’ question of the next decade,” he says.

I asked Professor Krosnick how he plans to share his findings, lest they merely languish in academia.

“I think that we social scientists have done our part in documenting public opinion,” he replied. “But a remarkable number of Americans, including representatives in Congress, are not yet aware of the public consensus on this issue. Perhaps billboards displaying the results of reliable surveys would help educate the public about itself.”

Call to action: Among you, readers, I know we have expert creative communicators. Please consider this an invitation to create such billboards.

Photo: Flooding in Houston, by David J. Phillip/AP via NPR.org.jpg